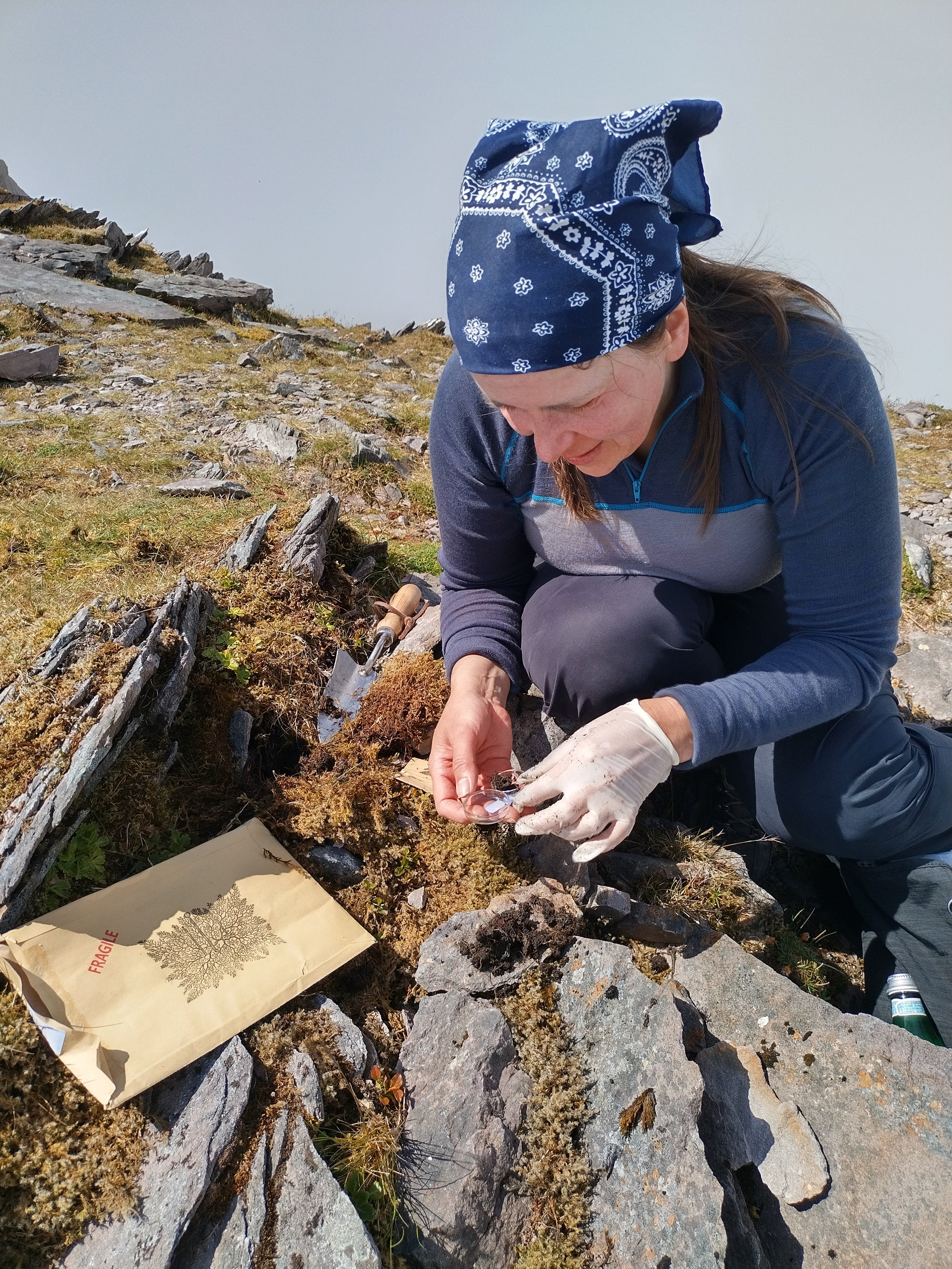

The Soil Project was a yearlong residency and project commissioned by Butler Gallery in Kilkenny Ireland. The General Soil Map of Ireland became the starting point for my research. In its two-dimensional representation, the limestone karst of the Burren in County Clare was keyed into the map as pink amorphous blotches, peatland was classified in purple-spotted clumps and large tan swaths outlined the coast of Cork. Captivated, I tried to visualize these soils and wondered what a material soil map of Ireland would look like, smell like, feel like. However, when the residency began, the country was in a phase of 5K Covid-19 travel restrictions and it meant I couldn’t access these soils directly. In order to develop a participatory project that prioritized direct engagement with soil, albeit remotely, I devised a postal art project. Packages containing a glass petri dish, detailed instructions for how to gather, sense and identify local soils as well as a copy of the General Soil Map of Ireland were sent to over 100 people from around the island.

As I waited for the soil packages to return, the studio research centred on biota, namely earthworms and mycelium, as essential to the formation, maintenance and restoration of high quality, indispensable soils. I appropriated scientific methods, making Evan’s boxes or 2D glass fronted terrarium, to observe the burrowing activities of earthworms, documenting their movements through multiple layers of soil, leaf litter, gorse and heather flowers, manure, wild garlic and decaying beech wood. Over the course of a few weeks, I created a time-lapse video of their often-unseen labors, making visible their role in decomposition, nutrient cycling and humus formation and highlighting soil as a beautifully complex, finite resource.

I began to trace the connections between individuals who reached out to take part in the project. Pinpointing these relationships onto the General Soil Map of Ireland, created by Teagasc in 1980, I could see relationships unfolding- between people and communities engaged with permaculture, organic food production, between artists and citizen scientists. A resulting web emerged like mycelium, with central nodes referencing the wider Butler Gallery community, artists invested in ecological relationality, students from the Burren College of Art and the National College of Art and Design, as well as soil enthusiasts from the Carrig Dúlra Permaculture course, Klaus Laitenberger’s Organic Polytunnel Growers course and multiple students from a Horticulture course at Technical University Dublin.

Many people sent back more than just the soil samples. Envelopes included postcards, personal letters, poems written on birch bark, dried flowers, geological survey photographs, images of others artistic practices and even paper made from mushrooms.

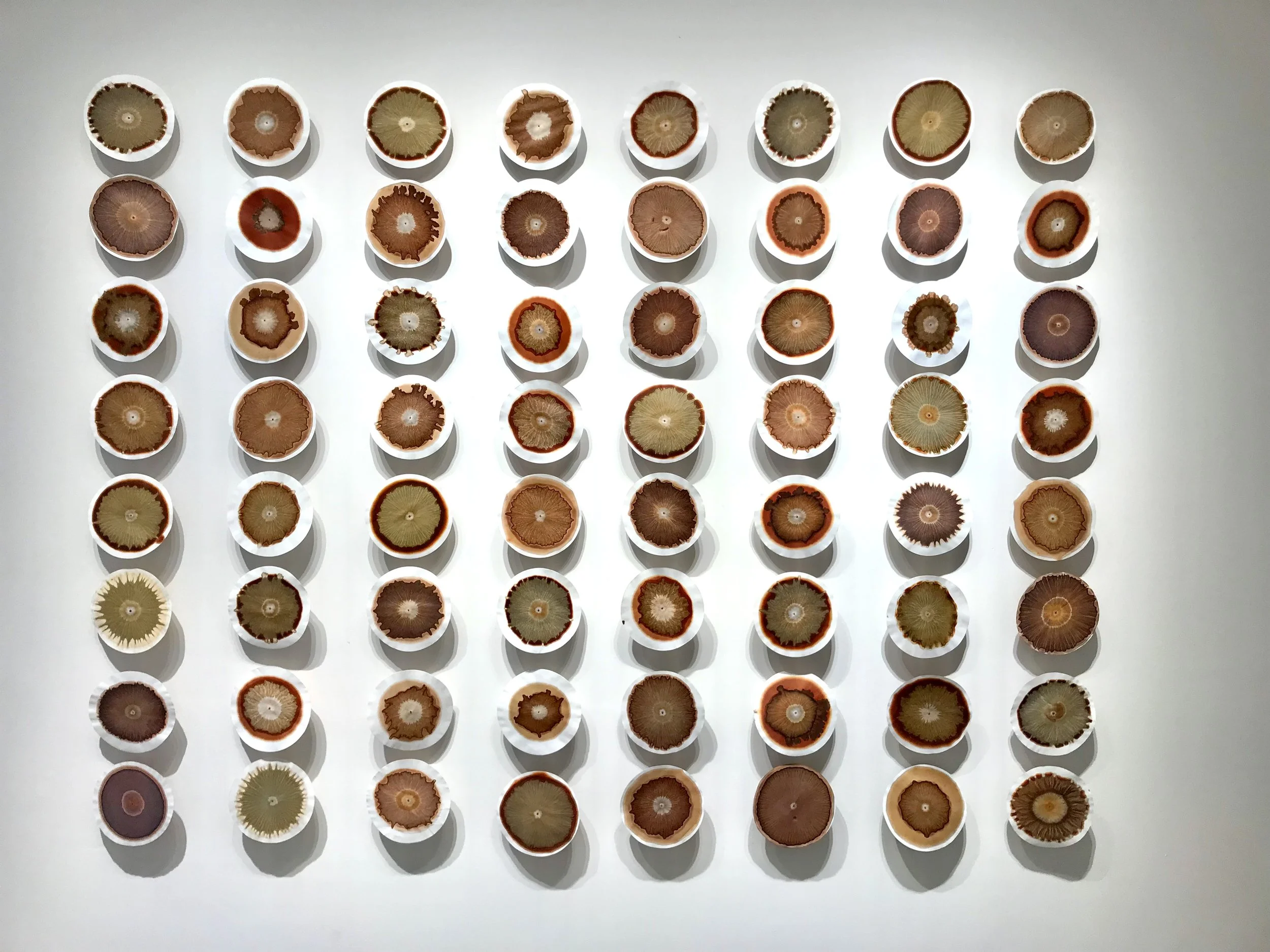

Initially, I was completely at a loss for how to transform the collection of material into anything as compelling as the original soil map. Searching for ways to visualize the complexity of life found within soil, I found a paper published by the Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management and University of Western Australia. From this I was able to recreate their methods in soil chromatography, an alternative photography process that creates a ‘soil portrait’ on light sensitive filter paper. First developed in 1953 by Ehrenfried E. Pfeiffer, a German soil scientist and advocate for biodynamic farming. Pfeiffer’s Circular Chromatography (PCC) became an inexpensive means for farmers and composters to view a snapshot of the biological activity and health of soil, compost, plants, and food. It is an accessible means for assessing soil structure, general health of soil, minerals available for the plant, biological diversity, or organic matter content and humus available.

At the end of the residency, 64 chromatograms were installed as part of a large scale, material soil map, that approximated each particular location’s soil composition. It was a collective mapping process, a “D.I.T., do-it-together as opposed to do-it-yourself,” artistic technology that sought to engender an inclusive and collective process of curiosity and engagement with local soils. This collective mapping process was in part inspired by Anna Tsing, author of The Mushroom at the End of the World who asks, How does a gathering become a happening that is greater than the sum of its parts?

A few of the socially distanced events held over the course of the year included a Fungi Foraging Walk with wild food expert, Mary Bulfin, a soil chromatography workshop I led with Phd candidate Katerina Gribkoff and an online conversation with curator Hollie Kearns and Merlin Sheldrake.