In 2015, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation declared the ‘International Year of Soils’ expressing concerns that the “finite non-renewable resource on a human time scale [is] under pressure of processes such as degradation, poor management and loss to urbanization”. More recently soils have become the focus of both academic research and media coverage that highlight that this vital resource that builds up over thousands of years has been a resource of value extraction for human consumption, and with the expansion of industrial agricultural practices is increasingly considered an endangered multi-species living world in need of ecological care.

When I first undertook the Soil Project Residency, the country was still in a phase of 5K travel restrictions. In order to develop a participatory project that prioritized direct engagement with soil, albeit remotely, I devised a postal art project. Packages containing a glass petri dish, detailed instructions for how to gather, sense and identify local soils as well as a copy of the General Soil Map of Ireland were sent to over 100 people from around the island. From this collective mapping process, I have created a series of experiments in soil chromatography to represent each gathered soil sample. This alternative photography process creates a ‘soil portrait’ on light sensitive filter paper that is both formally beautiful and a useful way to assess the soil for organic matter, biological diversity, minerals and humus. The individual chromatograms will be installed as part of a large scale, material soil map.

The archive of the postal art component of this project will also be displayed alongside additional research phases of the residency that focused fungi and earthworms as essential biota that contribute to the formation, maintenance and restoration of high quality, indispensable soils.

This project comes out of an annual commission by the Butler Gallery for The Soil Project Residency, which supports invited artists to create participatory projects which connect deeply with the environment, the world around us and the soil beneath our feet.

Soil Collecting packages were sent to over 100 people from 19 counties around the island. Many people sent back more than just the soil samples. Envelopes included postcards, personal letters, poems written on birch bark, dried flowers, geological survey photographs, images of others artistic practices and even paper made from mushrooms.

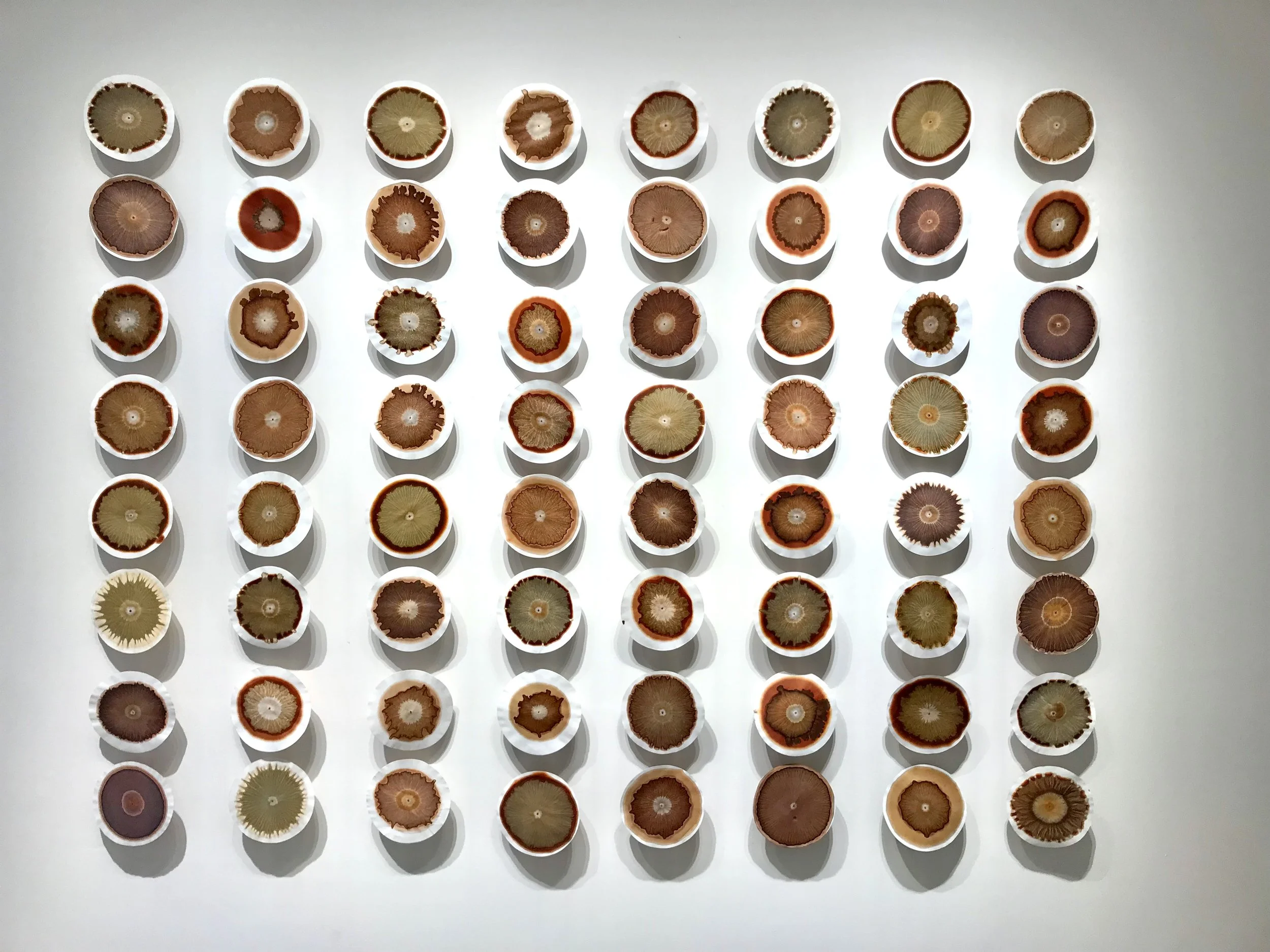

From this collective mapping process, I have created a series of experiments in soil chromatography to represent each gathered soil sample. This alternative photography process creates a ‘soil portrait’ on light sensitive filter paper that is both formally beautiful and a useful way to assess the soil for organic matter, biological diversity, minerals and humus. The individual chromatograms are installed as part of a large scale, material soil map at Butler Gallery's Learning Centre.

Spore Prints within spalted beech frames, made from two solid planks of wood

A Foraging for Fungi walk around Kilkenny and the castle grounds with Wild Food Mary Bulfin.

My research into the role that soils play in maintaining and supporting a sustainable environment considers how other lifeforms, such as earthworms and mycelial networks, influence and sustain soil vitality. The quick time-lapse video shows several species of earthworms within an Evans’ box or 2D glass fronted terrarium, as they burrow through multiple layers of soil, leaf litter, gorse and heather flowers, manure, wild garlic and decaying beech wood. While the video prioritizes the often unseen labour of earthworms in terms of decomposition, nutrient cycling and humus formation, it also seeks to highlight soil as a beautifully complex, finite resource .